Parviz Kimiavi

Parviz Kimiavi (born 1939, in Tehran) is an Iranian filmmaker, screenwriter and editor. Despite contributing few films to Iranian cinema, his impact on the Iranian new wave was essential. His films had elements of surrealist, documentary, ethnographic and experimental cinema. On one hand, his modern and playful style and on the other his affinity for mad or isolated characters as well as Iran’s dilapidated culture, made Kimiavi’s work remarkable among other Iranian films.

Like most of his contemporaries, Parviz Kimiavi started his career in film by making documentaries for the Iranian national television. From mid 1960’s onwards, many students began returning home from studying abroad and started their careers in film and television, including: Fereydoun Rahnama (France), Sohrab Shahid Saless (Austria), Bahman Farmanara (U.S), Dariush Mehrjuyi (U.S), Kamran Shirdel (Italy), Khosrow Haritash (U.S) and Hajir Darioush (France). The arrival of these young filmmakers at the time resulted in a vast inpouring of various cinematic styles from different countries. Among these filmmakers, Parviz Kimiavi was undoubtably the most French; a filmmaker clearly inspired by Avantgarde, surrealist and French new wave cinema. Much like the greatest French filmmakers, he could challenge the medium by breaking the rigidity of form, as well as adopting their cynical, playful and biting content. In his very first documentary, “The Hills of Qeytariyeh” (1969), we can see the filmmaker’s open and free style intwined with his playful approach towards history. Although this documentary depicts one of the greatest archeological discoveries in the world, it never takes on a serious or scientific stance and even mocks itself at times.

Like most of his contemporaries, Parviz Kimiavi started his career in film by making documentaries for the Iranian national television. From mid 1960’s onwards, many students began returning home from studying abroad and started their careers in film and television, including: Fereydoun Rahnama (France), Sohrab Shahid Saless (Austria), Bahman Farmanara (U.S), Dariush Mehrjuyi (U.S), Kamran Shirdel (Italy), Khosrow Haritash (U.S) and Hajir Darioush (France). The arrival of these young filmmakers at the time resulted in a vast inpouring of various cinematic styles from different countries. Among these filmmakers, Parviz Kimiavi was undoubtably the most French; a filmmaker clearly inspired by Avantgarde, surrealist and French new wave cinema. Much like the greatest French filmmakers, he could challenge the medium by breaking the rigidity of form, as well as adopting their cynical, playful and biting content. In his very first documentary, “The Hills of Qeytariyeh” (1969), we can see the filmmaker’s open and free style intwined with his playful approach towards history. Although this documentary depicts one of the greatest archeological discoveries in the world, it never takes on a serious or scientific stance and even mocks itself at times.

P Like Pelican” (1972) is Kimiavi’s most important and most beautiful documentary; a film that inspires Iranian documentarians decades after its release. This documentary contains many of the filmmaker’s main motifs: ruination, madness, progression, solitude and fantasy. “P Like Pelican” tells the life-story of an old man called Seyed Ali Mirza, who has been living alone in the ruins of Tabas, after a devastating heartbreak forty years prior. Children often visit him, sometimes to make fun and other times to show him affection; they even take him to the city to look at a white pelican. The final scene of the films is the old man’s encounter with the pelican, which somewhat sums up Kimiavi’s cinema: an encounter between ruination and fantasy. A meeting between what’s lost and what’s imagined. An encounter between French cinema and the reality of Iran. As exemplified in the film, Kimiavi is interested in characters who’ve been left behind and all alone from long ago. Straggling characters who also have a prophetic nature and can predict the future like the classic archetypical madman. In order to believe in the prophetic abilities of Kimiavi’s characters, we just need to remind ourselves of the fact that six years after “P like Pelican”, Seyed Ali Mirza dies in the Tabas earthquake and lies buried in the ruins of Tabas for almost thirty years.

Almost all the protagonists of Kimiavi’s cinema are madmen and outcasts of society, living in their own delusional dreamland. In one of his interviews with Hamid Nafisi, Kimiavi claimed he was fascinated by isolated and lonely figures in his adolescence. He goes on to recall a his first school essay which was about a bald and blind bean seller in a corner of Neishapur’s grand bazaar. He also made a film in France after the revolution about a madman who’s lived in an abandoned trench from World War II. Kimiavi’s most prominent madman is the character of Darvish Khan in “The Stone Garden” (1976). A deaf and mute man, who after losing all his trees to drought, hangs stones from the tree branches and takes care of them like ripe fruit. Darvish Khan, like the rest of Kiamiavi’s madmen, is left behind from another era and is contradictory to the very nature of the progression. His inability to hear or speak could signify the censorship of the Pahlavi regime; an era where stuttering, mad and blind characters were plenty in Iranian cinema. Darvish Khan wants to hang himself from his stone trees and give us a tragic finale, but fortunately, Kimiavi’s playfulness disallows him from doing so: he hangs himself by the feet.

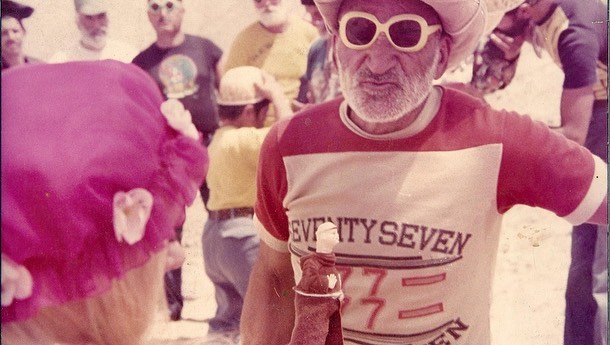

The Mongols” (1973) is among Kimiavi’s more recognized and acclaimed works. A film massively influenced by French cinema and especially Kimiavi’s favorite filmmaker, Jean-Luc Godard. The influence is not limited to its freeform, modern and exuberant nature, but Kimiavi criticizes television and other forms of mass media like Godard. The story revolves around a couple that don’t have a lot to say to each other, but are somewhat connected in what they do: the woman is doing a historical research on the Mongolian invasion of Iran, and the man is examining the destructive effects of television on the country’s culture. The film applies the same approach to both the Mongols and television, and manages to criticize the colonist ways of old (Mongols) and the consumerism of the modern era (television). It’s interesting that Kimiavi, again like Godard, criticizes himself as well and references his own work numerous times. If we exclude the work of Abbas Kiarostami, we can claim that there is no other film that rivals “The Mongols” in self-referencing and self-reflection. For example, in a scene the Mongols complain about how the film is being made, and in another scene, Kimiavi places his neck on a guillotine in an implicit reference to the censorship of the Pahlavi era. The filmmaker not only references his previous films, but summons some their characters in the film.

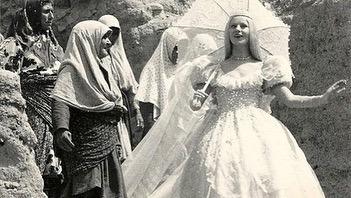

“OK Mister” (1978) is Kimiavi’s final film. The film’s protagonist is an American merchant called William Knocks Darcy, (played by Farrokh Qafari) who signs the first oil commission contract, which was more a hoax than a contract. In “OK Mister” Kimiavi depicts how the introduction of oil resulted in the ruination of Iranian society as it was morphed into a westernized, consumerist society. The film takes a hard anti-imperialist stance and criticizes the emergence of western culture in Iran with a cutting and playful tone. Ironically, the film was not screened during the Pahlavi regime as the revolution was ongoing, and was also denied screening permission in the following “anti-imperialist” regime for different reasons. Perhaps Kimiavi himself has come to the conclusion that criticizing the general concept of the west can lead to dangerous places.