Dry & Moist

Olaf Brzeski

Curated by Alireza Labeshka

KAAF’s first production project by Polish artist, Olaf Brzeski in cooperation with Raf Projects and Poland Embassy Tehran

September 20-Novembr 20, 2014

Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMOCA)

Having two artist residencies in Tehran enabled Olaf Brzeski to view the city through his intuitive perspective. He draws a kind of Geography of Desire in restricted culture of a middle east city, and he focused again on his main current concern, desire, in the context of Tehran. His study lead him to make a big metaphorical sculpture made out of natural elements like clay (adobe) which is reminiscent of materials used in traditional houses in central dry Iran and Tehran, trees’ moist branches and leafs. It seems he found a forgotten treasure, desire, in a box, hung out of mud, out of which is associated with sin in a dry and neat context.

‘Dry and Moist’ exhibition will be hold in Sculptures Court of Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art for two months begins from 16 October 2014.

Exhibition Text

Catching the Uncatchable

+ Olaf! There’s only ten days left to display; we have to provide the premises; so what are you going to do…?

+ Give me time till tomorrow afternoon; I will tell you then.

+ Well, everybody is worried, there is not much time left…

+ We will do it … I want the moment to come.

And these respites granted in the process of making “Wet and Dry” happened again and again till “the moment” – which I know more about now – happened and you can see the final work of Olaf in the courtyard of sculptures in the museum of contemporary arts. Olaf Brzeski came to Iran for eight or nine days in December 2013. I have told the story of how we met many times and I am not going to do it again; we wanted to present his works in Iran, but he intended to visit the location first, go back and read, and then come back again and this time produce the work in Tehran in his three-week residence. This “going back and reading” and the anticipation for “the moment” took nine months; it was like he was pregnant with a thought, an idea and conversations such as the one you read above. It had no benefit but to increase the labor of delivery; “the moment” had to come.

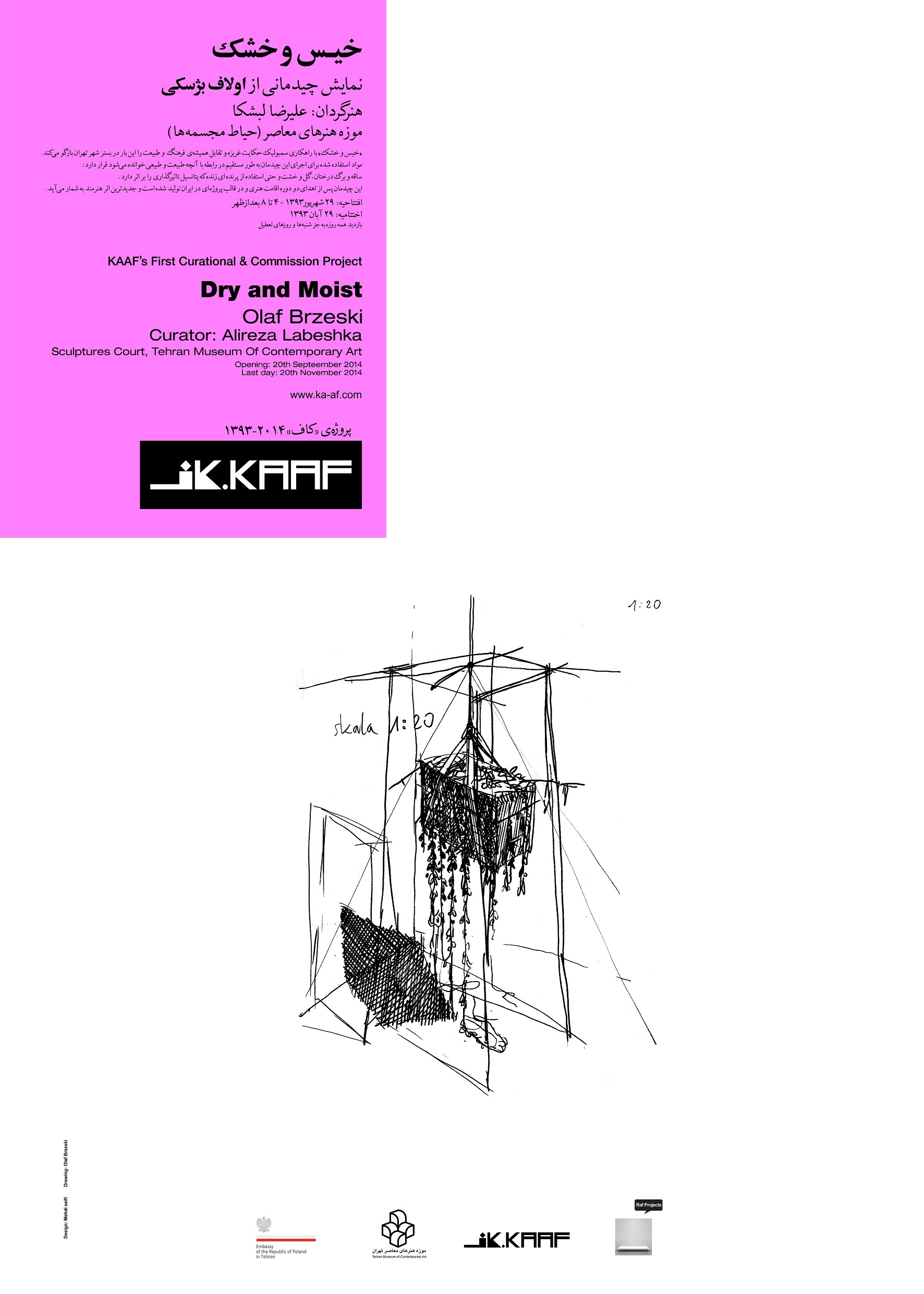

From a general view, this work could present catching “the moment”. Olaf’s response to our request was within the work itself, the trick was letting the process of making the work be the work itself. This box has been pulled from someplace, pulled hard, forcefully, dirty and drenched of the idea. The fact that the work itself is like a 3D drawing somehow informs us of the proximity between the drawing and the thought. “If you want to rub a bank, you take a lot of time trying to make a plan. You think to yourself where the guards might be standing, where the vault is, from where should you enter, and from where should you flee. There is no way you won’t draw these thoughts on a paper. Especially if you want to do it with a few more people, you have to explain the plan with these drawings”, Said Olaf. In lots of Olaf’s works, we witness the process of catching the idea and because of the proximity between the drawing and the thought, he has to convert the drawing to sculpture with no alterations. Now you are facing the incarnation of an idea. An incarnation that has tried its best to resemble its origin: the thought, or in the materialistic sense: the brain.

But Olaf didn’t read about Iran for nine months just to explain the process of his works. Now he knew more about politics, culture and social issues of Iran than he did before. He had felt the media’s behavior and different narratives and the separations of worlds, but like all of his other works, he had his own narration of the phenomenon; a narration retrieved from his interactions with the friends he had made in Iran. For him, it didn’t matter that in Iran women have to wear scarf or some newspaper is banned because of some article. He followed the news about these issues or he thought there is nothing to judge, at least not for him, or maybe he wasn’t interested in judging. Instead of all these, he was thinking about what was inside. Something that he was sure of: instinct, nature, desire … Instead of caring about all the intellectual issues that he saw in the all works of his Iranian colleagues, he cared about a more fundamental issue that we were missing. Instead of responding to the expectations of the current artistic dialect, Olaf Brzeski brings to the table a new issue, which at the same time is a very old issue. “I want to take out the instinct like a treasure from the mud of my brain”. Again he cares about the origin, the source. As if against all that culture, he brought our attention to all the nature. To understand how this work is referring to desire, we need to review Olaf’s earlier works. But unlike his other works for which he used materials like iron or clay, this time he uses foliage. He built his work’s background with clay. And finally he uses a chicken to connect this pulled out box – that is hidden for years like a treasure – to reality, a chicken that doesn’t do anything but eat and excrete, and all of these mean instinct, nature, desire…

Another very important matter is the place the work is installed in, the courtyard of the museum of contemporary arts, located in the center of the city. In his visits, Olaf paid attention to this matter that if there is going to be any pleasure or satisfying any desire, it has to happen around the city not in the center and he always had a question in mind that why in here you have to hide the desire in the closets of the house. Olaf Brzeski is fully aware that why a chicken would be part of his work and without it, this work would be undone. This chicken not only simplifies the understanding of a metaphor and the retrieval of the source, but also its walk in the center of the museum of contemporary arts is a loud scream to address us about what we are missing or we don’t look for in the middle of a museum.